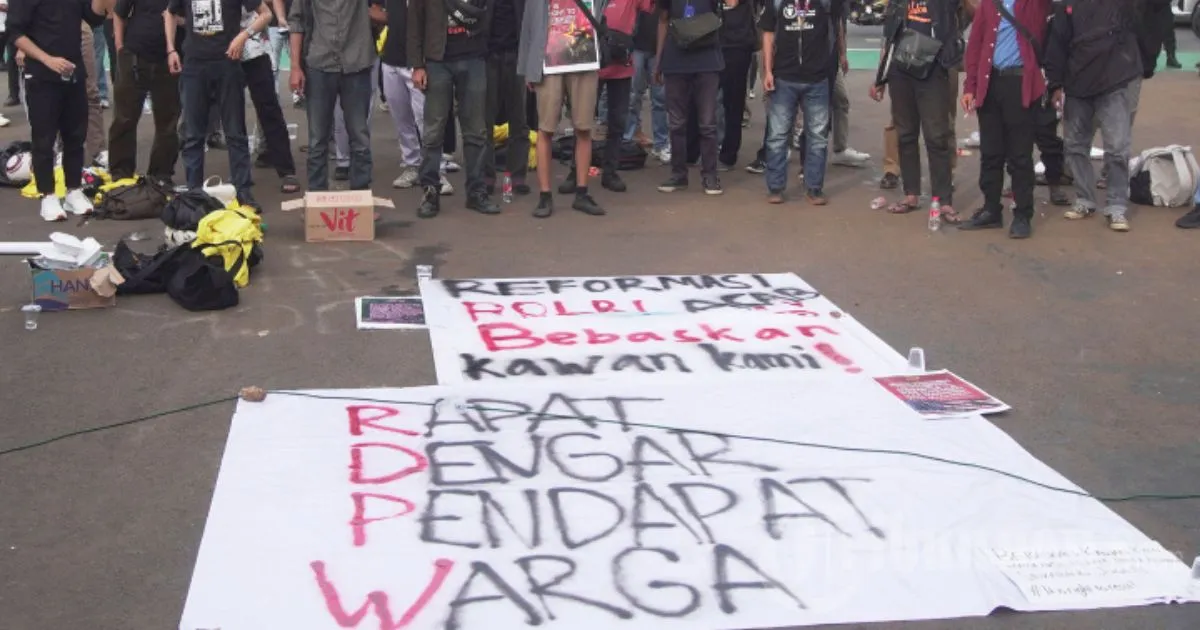

Jakarta. Something interesting happened in front of the House of Representatives (DPR) building in Jakarta on Monday (October 6, 2025). Alongside the Citizens’ Hearing (RDPW) held by the University of Indonesia Student Executive Board (BEM UI) in front of the legislative building, several protesters also set up a book reading stall.

Of course, the students weren’t trying to sell books. Symbolic criticism accompanied their main activity, namely actions or demonstrations in the form of RDPWs.

Even though not a single member of the DPR was present, as a political and cultural event, the BEM UI action could be called a success.

The incident was covered by the mass media and went viral on social media. And, no less important from a cultural perspective, the students’ actions became part of a cultural dialectic.

In my opinion, as a symbolic critique, it was very clever of them to open a book reading stall alongside the demonstration. The substance of their criticism is very fundamental.

It is not just a criticism of the police who some time ago confiscated books suspected of being closely related to the riots in the Surabaya and Sidoarjo areas.

Some of the books confiscated by the police were titled “What is Communist Anarchism?” by Alexander Berkman; Che Guevara’s Guerrilla Warfare Strategy; Jules Archer’s “The Story of Dictators”; Franz Magnis-Suseno’s ” The Thoughts of Karl Marx: From Utopian Socialism to the Dispute of Revisionism” ; and Emma Goldman’s ” Anarchism: What We Really Struggled For .”

The police said the confiscated books contained ideas about anarchism and communism.

The police finally returned the books belonging to the suspects in the East Java riot case at the end of last September, after concluding that there was no connection between the books and the crime being investigated.

However, the public is wondering whether the police are indeed lacking in literacy. The return of the books is not due to investigators finding no connection between the books and the crimes under investigation, but rather to the recent strong calls for police reform.

We know that President Prabowo Subianto responded positively to calls for police reform. The President promised to establish a National Police Reform Committee.

The public also knows that the National Police Chief, General Pol Listyo Sigit Prabowo, even preceded this by forming a National Police Reform Transformation Team consisting of 52 police officers.

Therefore, it’s reasonable to interpret the return of the books as mere lip service. The public hasn’t yet seen it as a reflection of police reform, which is entirely based on changes in perspective and behavior as a product of literacy maturity.

For me, the students’ action of opening a book reading stall at the same time as the demonstration in front of the DPR Building is a blow to the foundation of culture.

In particular, they criticized the political traditions of the modern Indonesian state which had moved away from its origins.

Indonesia’s state tradition has been criticized for no longer being guided by intellectual maturity, symbolized by books. Political elites and state administrators are considered deaf, mute, and inactive, due to a lack of imagination and thought due to a lack of literacy.

In fact, Indonesia is a modern nation, a product of the strong literacy of its founding fathers. Indonesia was not a gift from colonial powers. It was woven together by the strength and intellectual maturity of its founders.

They, the founders of the nation, were a generation that successfully celebrated literacy in very limited situations.

They read, wrote and debated through newspapers and literary works about their time with passion.

True literacy has proven to produce a tradition of criticism, open-mindedness, and imagination that transcends its time.

The results were truly remarkable, extraordinary, and out of the box . Their literacy marked a “renaissance,” guiding the “movement” of the colonized people, the dawn of Nusantara culture.

This literacy gave birth to a new community that called and was called the “Indonesian nation”, a reflective and visionary masterpiece, which would later proclaim its independence and form a nation with all the constitutional instruments of a modern democratic state.

Let us take one aspect of this masterpiece, namely Pancasila, which was agreed upon as the foundation of the state through a sharp debate that demonstrated intellectual maturity.

Pancasila could not have been born without intellectual maturity, without genuine literacy. Bung Karno said it was “dug” from the soil of Indonesia.

Without strong literacy and a strong tradition of criticism, it would be impossible to understand the great ideas of Indonesia, both their strengths and their weaknesses.

Pancasila was successfully agreed upon, both in substance and text, through intense debate. This was only possible by people raised in a culture of good and sincere literacy.

The tradition of criticism is the offspring of the tradition of literacy. Literacy without criticism will not yield reflection, will not yield the syntheses necessary for the renewal of civilization.

The tradition of criticism that grew from a good and sincere tradition of literacy is what disappeared in this country precisely when this nation had to fill its independence.

Culture and civilization are not moving forward, but are stagnating, even regressing back to the dark ages of colonialism.

The confiscation of books marked that dark era. This country has a literary legacy full of irony, the effects of which are still deeply felt today.

Let me take just one example: the works of Pramoedya Ananta Toer. Has our subconscious fully recovered and become clearer when viewing Pramoedya’s works?

Have we (the country) appreciated Pram’s quality works and preserved them for the enrichment of Indonesian literacy?

The history of Indonesian literacy is sad and poor. Pram’s writings were admired worldwide, reprinted many times, and translated into many foreign languages, but were banned, banished, and condemned at home.

Instead of being made compulsory reading for school children, Pram’s works were removed from the public’s reach, especially the younger generation.

The younger generation should be asked to devour quality reading material as a source of character building, but instead they are kept away from these works.

Public fear of Pram’s work was deliberately created. Through this fear, the public’s mind was controlled, controlled. No other thoughts were allowed. At the same time, the thoughts of those in power were deeply instilled.

The New Order rulers did not care that Pram’s Buru Island Quartet was a quality literary work with a colonial era setting that was actually good as a source of national literacy.

The New Order also did not care that the world appreciated Pramoedya for the quality of his humanitarian thinking.

Public fear is so profound that it naturally shapes public choices. I believe the police’s approach to confiscating books reflects this.

It is strange that the book Karl Marx’s Thoughts: From Utopian Socialism to the Dispute of Revisionism by Franz Magnis-Suseno, published after the New Order collapsed, was also confiscated.

In my opinion, this book really helps the Indonesian public understand Karl Marx’s thoughts which shook the world.

Confiscating the book is like blocking the path to Indonesian culture and civilization, even belittling the nation’s founders who could not have imagined a Greater Indonesia without reading the works of Karl Marx.

The impact was profound and is still felt today. The changes initiated by the 1998 reforms have proven to be stagnant (involution).

Many of the problems left behind by the New Order remain unresolved. Democratic consolidation has been slow and has not achieved the desired results. Changes in political institutions have not been accompanied by strengthening democratic values, and the people have not been empowered politically.

On the other hand, the arbitrariness of the rulers (elite) seems to be allowed, protected, justified.

As the result, corruption is rampant, the distribution of welfare and justice is uneven, and the ideals of independence are far from reality.

Unlike the past before colonialism, which was able to create Borobudur and other masterpieces, and the early days of independence, which were able to create Pancasila, the 1945 Constitution, and lead Asia and Africa, now Indonesia lacks works that are admired by the world.

In contrast, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) has named Indonesia’s 7th President, Joko Widodo, a finalist for its “Person of the Year 2024” award for the organized crime and corruption category.

Despite championing the ousted Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad, OCCRP’s decision is a slap in the face and deserves serious reflection.

The students in front of the DPR Building yesterday reminded us, especially those in the DPR Building and the elite leaders of this country.

Indonesia’s existence and the future imagined by the nation’s founders are threatened, because they abandoned the foundation of modern civilization, namely books and their offspring in the form of the tradition of criticism.

Comments